There have been new developments since I wrote about privacy concerns with the Summit online platform in September for the Washington Post Answer Sheet. I followed that up with a longer piece on this website of the Parent Coalition for Student Privacy, with criticisms and observations of parents at schools using the platform, saying that their children have become frustrated, bored, and disengaged as a result of spending hours each day in front of computers, receiving very little feedback from their teachers.

Summit charter schools and their online platform, now used in over 300 schools across the country, both public and charter, have received millions of dollars from Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg; Zuckerberg has pledged to support the continued expansion of the online platform through his LLC, the Chan-Zuckerberg Initiative.

Shortly after my Washington Post piece appeared, I was contacted by Diane Tavenner, the CEO of Summit charter schools, who asked if we could meet when she was visiting NYC. I agreed. We had lunch on Sept. 15, and I handed her a list of questions, mostly about Summit’s privacy policy, most of which my associate, Rachael Stickland, had already sent to Summit staff that she had met at SXSW Edu the previous March, and to which she’d never received a response.

Diane was perfectly pleasant, and emphasized her commitment to students and the value of the program, but offered few substantive answers to any of the questions I asked her at lunch. When I asked her why Summit and the Chan-Zuckerberg Initiative felt the need to collect so much personal student data without parental consent, and why they couldn’t just offer the platform to schools if it was so helpful, she replied, “What do you think we’re doing with the data?” I responded, “you tell me.”

When I asked her why Summit believed they could claim the work of public school teachers uploaded into the platform without compensation, she said that there were no schools where teachers hadn’t voluntarily agreed to use the system, and Summit’s right to their work was understood by them as the cost of participating in the system.

I asked her why in one place in the Summit privacy policy, they promise not to sell student data, but in another part of the document, they claim the right to transfer the data in an “asset sale.” She said she would ask her people. Since our meeting, I haven’t heard anything more from her on any of these issues.

During the lunch, I mentioned that I was going to be in Oakland the weekend of Oct. 14- 15 for the Network for Public Education conference, and that I would be interested in visiting some schools after that are using the Summit platform. I said I was especially eager to visit public schools, since I’d heard from many public school parents in five states who told me their children had negative experiences with the program. These parents were upset that Summit had withdrawn the right of parents to consent to the system shortly after CZI took over, and they were concerned about how their children’s personal data was being shared with Summit and then redisclosed with unspecified other third “partners” for unclear purposes.

Diane later emailed me and said that I could visit Summit Prep charter school on Oct. 16, in Redwood City, their flagship school. An Uber would come and pick me up at my Oakland hotel, she said, and the drive would take about an hour each way.

I pointed out to her that according to the list on the Summit website, there were several public and charter schools in Oakland near the hotel where I was staying that had adopted the platform, as well as several Summit charter schools just ten minutes away. Why couldn’t I visit any of these schools instead?

She responded that the principal of one of the Summit charters near Oakland was on maternity leave, and she didn’t want to put any more pressure on the school. At the other two nearby Summit charters, she explained, the students would be on “expedition” that afternoon, visiting their out-of-school “partners”. She didn’t explain why we couldn’t visit any of the other public and charter schools using Summit platform in Oakland itself.

Having no other choice, I accepted her invitation to visit the school in Redwood City, suspecting that this school was probably offered because it exemplified the best model of how the platform was operating. On Oct. 16 I was met by an Uber driver at my hotel, and we traveled south to Summit Prep, through the haze that was issuing from the fires then burning miles north in Sonoma and Napa.

At Summit Prep, I was met by two school leaders, and we talked in an empty office for about a half hour, where they explained to me about the platform and how it was designed. Then we briefly toured two classrooms. In the first classroom, there were about thirty students engaged in “Personalized Learning Time”, gazing at computer screens and working on their individual “playlists.” These playlists include content in different “focus areas” delivered via various mediums, including online texts and videos. When students have learned these materials, they’re supposed to take multiple choice online tests to show they’ve “mastered” the area. In addition, in each of their courses, there are projects they are supposed to complete.

This is how it is described on the Summit website: During PLT, students grab their laptop and log into the Summit Learning Platform where they can view their goals, their projects, and their classes. During PLT, students work through their playlists at their own pace, and take assessments for each focus area when they feel they’re ready.

All the students were silently and solemnly staring at computer screens. When I walked around and looked more closely, some were apparently researching projects in evolution, others were looking at a math problems, and still others were looking at Facebook pages or other websites which they hurriedly switched off when I passed by. There was one science teacher towards the back of the room, talking to two students, but otherwise there was no student or teacher interaction in evidence.

While the projects have a specific deadline, as I had heard earlier from the school leaders, their “content” assignments, including passing online tests, do not. I asked why this was the case, since it might be difficult for students to research their projects adequately without first learning the content or the underlying “facts” in any focus area or subject. The school leaders explained they wanted students to set their own pace in absorbing content, but the projects had deadlines as students were supposed to collaborate with one another on this work.

I visited another classroom where 12th graders were engaged in peer-reviewing essays they had written at the beginning of the class, grading them according to the Summit’s complex rubric of cognitive skills. When I asked why the essays were written on paper rather than on computers, the school leaders told me that this was because they were practicing for the California state exam in which students are asked to write essays on paper.

I noted that I had seen no classroom or small group discussions. The Summit leaders said that was because none were occurring during my brief visit. It is true that the amount of time I spent in classrooms wasn’t sufficient to make an informed judgment either way, but what I saw did not encourage me.

When we returned to the office, I questioned why delivering content primarily online was an effective method of teaching. Shouldn’t learning happen in a more interactive fashion, with the material presented in person and then discussed, debated, and explored? Why did they have this comparatively flat, one-dimensional attitude towards content? And how could math be taught this way, given that math requires helping students learn how to solve problems in a more interactive fashion?

They told me math is taught differently, and indeed had to be taught through teacher-student interaction, but that this isn’t true of any of the other subjects, whether it be English, social sciences or physical sciences.

Yet teaching content primarily online and separating it from assigned projects seems to me a strange idea, and likely to lead to superficial learning and disengaged students, as many parents tell me their children at Summit schools often feel. Parents have also reported that because the online content and tests have no deadlines, their children often fall far behind, and are forced to catch up at the end of the semester by hurriedly taking multiple choice tests in many focus areas and subjects, rushing through in a panic.

I also mentioned to the Summit school leaders that I had been reading the latest Rand study which analyzed results at a subset of “personalized learning” schools, those called the Next Generation Learning Challenge schools that are funded by the Gates Foundation. I said that I assumed that Summit schools were a part of the study, since they are probably the most renowned of the NGLC schools. The school leader nodded his head in agreement.

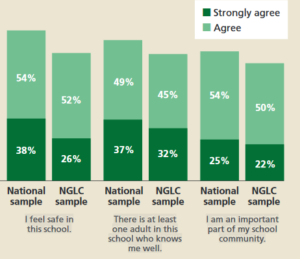

I recounted how the RAND study revealed that surveys of students at the NLGC schools were less likely to feel safe, less likely to say there was at least one adult at the school who knew them well, and less likely to feel they were an important part of their school community, compared to similar students at matched schools. These findings are depicted in this chart from the study on p. 24:

I pointed out that while advocates for personalized learning schools like to portray students at these schools as more engaged and more in control of their learning, the RAND survey revealed that these students were significantly more likely to say that that “their classes do not keep their attention, and they get bored” compared to similar students at other schools (30% to 23%). Only 35% of students at the NGLC schools said that “learning is enjoyable” compared to 45% of matched students. (These and additional survey results are from the appendix of the report .)

When I asked the Summit school leader if he thought the students are happy at their schools, he replied, “I think they realize they are engaged in productive struggle.”

The RAND study also found very small and mostly insignificant gains in test scores in the Next Generation Learning schools, which is somewhat surprising, since these schools have received millions of dollars from the Gates Foundation and other sources. The lead RAND researcher, John Pane, who has spent several years studying the results at personalized learning schools, in work funded by Gates, was recently quoted in Ed Week as saying “the evidence base [for them] is very weak at this point. ”

Since I’ve returned home, I have been contacted by teachers and parents at Summit schools with additional concerns. A teacher in Massachusetts wrote me that he has grave doubts about the platform’s suitability for students at his school, particularly those with disabilities and English Language Learners.

Parents in Cheshire, Connecticut have also contacted me, dissatisfied with the use of the Summit platform at their schools, with their middle school children spending many hours on computers in class, working on assignments of uncertain quality. They sent me a link to a document from their district Superintendent, called Summit Myths /Facts, which includes the following statement:

“The information we share with Summit is limited to student name, course and/or grade and email information for log-on purposes. We share no other personal data. Summit is also privy to student performance on the platform.”

Yet the Summit Learning Participation Agreement with Cheshire , which the parents also sent me, reveals that the district has agreed to give Summit access to an huge amount of highly personal information not mentioned above, including but not limited to student names, addresses, grades, test scores, race, disabilities, disciplinary history, personal goals and narratives, their communications with teachers and other students, scores on college admission exams, college attendance and work force records and more:

In the performance of the Agreement, Summit may have access to or receive certain information provided by Partner School that is not generally known to others….and includes, but not is limited to, Student Data (defined below) and other data that identifies a specific User, such as a name, address, student identification number, phone number, email address, gender, date of birth, ethnicity, race, disabilities, school, grade, grades and grade point averages, grade level promotion and matriculation, coursework, test scores, assessment data, highest grade completed, attendance, school discipline history, narratives input by students about their own goals and learning plans, communications with teachers and other students, notes and feedback o or about students, observations from students’ mentor about individual students, college admission test scores, AP and IP test information, college eligibility and acceptance, employment, Partner School financial information, and Partner School business plans.

All this data may be accessed by Summit and potentially shared with other unspecified third parties, without parent consent.

In addition, while the Summit agreement with Cheshire promises “No Marketing and Advertising to Students,” this is immediately followed by the following conditionality: “Summit shall not advertise or market to a student or his/her parents/guardians when the advertising or marketing is based upon any of that student’s Student Data that Summit has acquired through the Platform [emphasis added].” This is not the blanket prohibition of advertising or marketing that the headline would imply.

And while Summit claims the right to access a wide range of sensitive student information, the Cheshire agreement also reveals that the corporation demands extraordinary secrecy when it suits its own interests. For example, the contract bars school officials from communicating any “Summit Confidential Information” to parents or the public at large, which it defines as “all technical and non-technical information concerning or related to Summit’s products, services etc.” The only individuals to whom the school can disclose any information about Summit’s products or services, including presumably their own views concerning the program, are other school employees who “are bound by non-disclosure obligations that are no less restrictive…”

If a member of the public requests information about the Summit program via a public records or Freedom of Information request, the school “shall notify Summit of such request promptly in writing and cooperate with Summit, at the Partner School’s reasonable request and expense, in any lawful action to contest or limit the scope of such requested disclosure.”

These contractual terms are unacceptable, and violate the obligations of the administrators at these schools to serve the best interests of students and taxpayers, in a transparent and accountable manner, rather than subject themselves to the corporate interests of Summit Charter Schools or Chan-Zuckerberg LLP.

These sorts of non-disclosure provisions have been seen in other contracts of ed tech companies, for example a non-disparagement clause in a New Classrooms contract that apparently prevented California school officials from criticizing the program. The Gates Foundation also tried to insert similar language into their service agreement with the NY State Education Department, which would bar the NY State Commissioner and other education officials from making any public statements about inBloom without prior written consent from the Foundation, even pertaining to information already in the public record. (I only learned about this demand –eventually rejected by NYSED –from FOILED emails I received after inBloom’s collapse. I received the emails more than a year after I had FOILed them, the day after Commissioner John B. King resigned to take a job at the US Department of Education.)

Cheshire Connecticut parents have now posted a petition to their school board, signed by 278 other parents, asking that the Summit pilot be suspended in their children’s schools The comments posted below the petition are especially illuminating about their observations about the negative impact of the program that they’ve witnessed on their children. Parents in the Fairview Park City School District in Ohio are demanding that the Summit Program be removed and that parents be part of the decision-making process from now on, in a petition signed by over 400 people, with 105 comments.

There is also an organized push-back against Summit in Pennsylvania, at Indiana area middle schools. Parents there have repeatedly urged their school board to stop the the program introduced at the start of the school year. A video of the December 4 school board meeting is here, and a reporter’s account is below.

Parents packed the board conference room elbow-to-elbow for the [school board] Academic and Extracurricular Committee meeting and committee members heard concerns for almost twice the usual one hour allocated for the panel’s agenda. Summit was all they discussed. Parents have protested at the board and committee meetings since early October…

Parents’ concerns have ranged from the complexity of the online program, increases in the amount of time their children spend looking at computer screens rather than listening to teachers, and their kids’ mastery of the subjects. Lately the board has heard an increasing number of complaints about the quality and appropriateness of the online resources, mainly YouTube videos, that Summit provides for the pupils to study…”

Yet the juggernaut that is Summit will be difficult to stop. The Silicon Valley Community Foundation gave $20 million to Summit in 2016. The Gates Foundation awarded Summit $10 million in June 2017, “to support implementation of the Summit Learning program in targeted geographies.” In September, the day before I met with Diane Tavenner, Summit was one of the ten winners of the XQ Super High School prize, receiving another $10 million from Laurene Powell Jobs’ LLC, the Emerson Collective, to create a new high school in Oakland .

And just a few days before my visit to Summit Prep, Betsy DeVos, the US Secretary of Education, visited a Milpitas public school using the Summit platform , also in the Bay Area. DeVos explained that the Summit platform “came with great recommendations” and that the “personalized learning approach was something we really wanted to get a handle on.” After her visit, DeVos said, ““I got to see creative approaches toward empowering students to take control of their learning.”